RUNNING TESTS

By:

On a sunny Friday afternoon in May, I’m sitting with Nicolaus Schafhausen in his office overlooking the Museumsquartier and the magnificent building of the Kunsthistorisches Museum. I hand him a self-made poster with over 50 questions from local artists, which I had collected from a Facebook call-out. Since he wouldn´t be able to answer all of these questions we opt for focusing on his vision for the Kunsthalle Wien as a publicly funded institution, the relationship between an artist and a curator and living and working in Vienna.

How do you see the function of the Kunsthalle Wien in today’s society?

Nicolaus Schafhasen: I think that in recent years, the genuine interest in approaching new forms of exhibition making and looking at contemporary art has shrunk. I’m not talking about the quota of visitors, but rather I see that today’s audiences expect to see what they already know. People would like to understand everything immediately. This is a huge problem. I see the role of Kunsthalle Wien as a place of “permanent research.” It should be acknowledged by the public that it is necessary to put ideas and works to the test and that’s why we are there. It’s about NOW, and not necessarily about art history.

Curatorial Ethics Conference: Vanessa Joan Müller and Nicolaus Schafhausen © Kunsthalle Wien 2015, Photo: Maximilian Pramatarov

Kunsthalle Wien was designed as an instrument of the city’s cultural politics and is almost entirely funded by the city of Vienna. Additionally, Austria as a country is a place with almost no smaller experimental institutions like those in Germany or especially in Switzerland, which were created by various associations such as Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt, Haus der Kunst in Munich, Deichtorhallen in Hamburg etc. Most of them were founded around the same time as Kunsthalle Wien.

At its inception no one saw the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, so the idea was to connect Austria, Vienna with the Western particularly Swiss and German art markets. Not necessarily the commercial markets but the market of exhibition making. Kunsthalle Wien was founded as a place of experiment and critique, also the critique of institution. It was, at that time, a very smart political move.

One should keep in mind that Vienna back then was a completely different city – 300,000 people less, with a seemingly homogeneous society. During this period many new museums were founded, reshaped and the popularity of contemporary art grew rapidly. So, today the Kunsthalle Wien has less in common with the initial idea at its foundation. Personally, I think it’s more of an international center for contemporary art in the same way as ICA, Palais de Tokyo, and other similar institutions. We are still around to experiment.

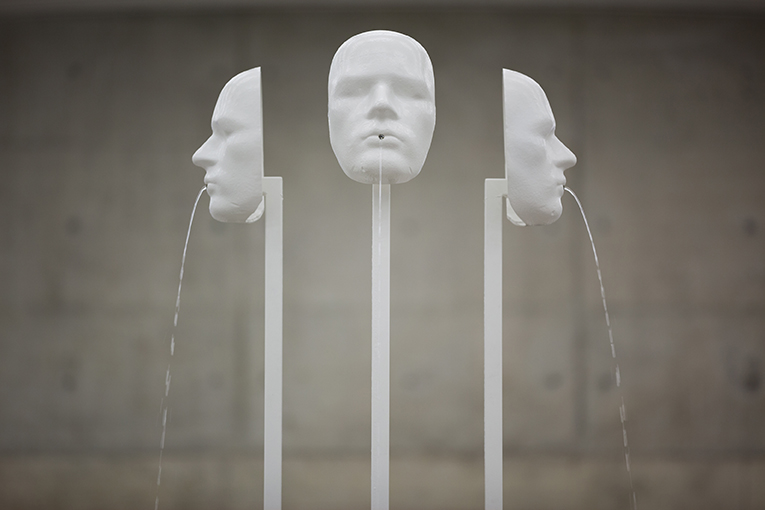

View of Exhibition New Ways of Doing Nothing, Kunsthalle Wien 2014, Foto: Stephan Wyckoff: Ryan Gander, You had the time, but I didn’t have the money, 2011, Courtesy gb agency, Paris; Marina Faust, Travelling Chairs, 2003–2010

Museums, the collecting institutions, also tend to experiment - often purchasing artworks for their collections immediately, trying to seize an opportunity to get the works while they still can afford them. Do you think it's a good startegy?

NS: Everyone wants to support one’s own structures or institutions. It seems to be typical of the times we live in. It has a lot to do with the pressure on individuals that they have to fight for their positions and institutions. It has definitely gotten more competitive. Daily life has gotten more competitive. We are living in very interesting times, that’s also why I am interested in this institution, because we are testing and figuring out how far those cultural, public instruments still make sense for our society. I´m pretty sure that the orientation of these institutions will be extremely different in 20 or 30 years, at the moment it seems that we are in a period of transit. It can’t be that in the future we exist only as representatives of the art system. This is definitely not enough. I could see that when we did the very first project here “What Would Thomas Bernhard Do,” which was an interdisciplinary festival focusing on central issues of our society and drawing on Thomas Bernhard’s tradition of critical, and sometimes unsettling thinking. The art scene as such had a problem with its format. It didn’t seem like they understood what we were doing. On the other hand, we had reached out to an audience of 5,000 enthusiastic people participating in the events, not necessarily from the arts. I expected something very different. I think these are clear signs that we should work on ways to improve the situation, going in the direction of the needs of society.

WWTBD – What Would Thomas Bernhard Do © Kunsthalle Wien 2013, Photo: Stephan Wyckoff

How do you know what society needs?

NS: I don’t, that’s why we offer such a diverse program. We see it as running different tests and we research and experiment to find out. We definitely do not ask people what they want and then put it on display or take it up in a discourse. When Kunsthalle Wien was founded, the politicians didn’t ask people if that’s what they wanted. That is the problem nowadays, that politicians ask people what they want. As a result, there are no new institutions, not many new models proposed in the last 20 years.

What strategies would you use to involve a broader audience?

NS: I think it is not possible to reach out to a broader audience with contemporary art. Nowhere, worldwide, is that the case. Only 5 to 10% of the population visit art institutions. It has a lot to do with education. It’s a pity of course. The mission of Kunsthalle Wien is not developing a program for children. Adolescents on the other hand constitute a very important target group and there are several respective programs in place. We do of course think about what value our work has for society – and it’s clear that we cannot reach everybody. However, I think that without such instruments like Kunsthalle Wien there would definitely be something missing.

Exhibition View The Miracle of Life © Kunsthalle Wien 2014, Foto: Stephan Wyckoff: Jos de Gruyter & Harald Thys, De Drie Wijsneuzen, 2013 (Edition 1/3), Courtesy: Isabella Bortolozzi Galerie, Berlin; and the artists

You are in the midterm of your appointment as a Director of the Kunsthalle Wien, could you reflect upon what is behind and what is still in front of you? How will you proceed?

NS: The strategy of the 1st year was more or less clear. It was about testing what works and what doesn’t. What was much more difficult than I thought was internationalizing the institution from within. When I started here, mostly all of the staff were native Austrians. This has definitely changed. We work with international curators, from France, Italy, Saudi Arabia, …. I understand institutions like this one as media systems, not only through social networks but also through how we communicate to the outside world. People who are working here work abroad; curating, teaching and giving lectures, and they transmit the message. This is what we expect from the local artists too, to “build bridges”, to borrow from this year’s ESC slogan. It’s always about building relationships, networks.

How do you facilitate this?

NS: Through our program; like the recently held “Curatorial Ethics” conference. This was very interesting. It was not about the 200 people who were there physically but the thousand or so people who watched it online. This is a new perspective for me that I find really exciting, to understand an institution as a media tool, as a kind of magazine that broadcasts points of view, opinions and research. Exhibitions are a point of departure for starting a discourse. We know that if we do a show like Isa Genzken, it’s much more popular than a show that we limit to only art discourse, but we sometimes succeed in departing from the art discourse and talking about broader issues, which are relevant for our society.

Installation view: I’m Isa Genzken, The Only Female Fool, © Kunsthalle Wien 2014, Photo: Stephan Wyckoff

Which of the projects that you realized at Kunsthalle Wien are you particularly proud of?

NS: “What Would Thomas Berhard Do,” I loved that project. I think it was very important and will have a follow-up in the form of a big festival in 2017. I was very happy with the “Curatorial Ethics” conference, the Isa Genzken show or, talking about a current project, the exhibition “Function Follows Vision, Vision Follows Reality” which deals with contemporary artists reflecting on Frederick Kiesler visionary ideas. I’m very proud of the reshaping of the institution, what it looks like now. I’m very happy and proud of the new team we have built. Of course, there are some exhibitions that are better than others, not each and every exhibition works, but I think that is normal.

Do you see yourself more as a curator or as a director?

NS: Curator, definitely. On the other hand, it has been quite good to have this double function, as it gives me more leverage in influencing when and where the money comes from. I think it’s important to understand how the system works. A lot of curators nowadays do not know and don’t want to know about what kind of limitations and conditions institutions have to operate under and where the money comes from. We managed to secure the budget of the Kunsthalle Wien until 2018, which is great.

Because I have done it for 20 years, I became pretty good at this, but the question comes up of where do I want to continue. There is an option that I could stay here for an additional 5 years, which under present conditions is an interesting perspective. I’m used to working with both small and big budgets, not to mention the free projects when no budget is involved. The most important condition is that the project is interesting and meaningful.

How has the curatorial work changed in the past 20 years?

NS: It has changed a lot. 20 years ago curatorial authorship was much more valued, now it is often seen as a competition.

Do you mean that artists nowadays have a very clear idea of how they want to present their work and see curators more as managers?

NS: Exactly. There are many artists I do not like to work with because they treat me like I’m just an organizer. Many of them I find good, interesting and relevant, but I do not necessarily have to work with them. Particularly in the case of solo exhibitions, I really want to make sure that this can be a good relationship for all the parties involved: for the artist, for the curator, and for the institution as well.

Why did you decide to take this post in Vienna?

NS: I found it an interesting challenge to reshape the rather populist institution that it had been before into something more meaningful. The program right now is only 2 years old and it will still take a while to achieve this goal. I also thought that it would be good for me to be in an environment that was shaped more by the east than by the west, which I was completely mistaken about. I knew Vienna from visiting it but not from working and living here.

Pierre Bismuth / Nicolas Firket The Grass is always Greener on the Other Side – New Vindobona © Kunsthalle Wien 2014

How do you see it now?

NS: Now I see it very differently. What was really new to me was that I, as a German speaking person, am considered a foreigner here. The idea of foreign I find preposterous. There is a rather self-centered mentality here, but at the same time people make themselves smaller than they are, most of the artists do, too, which I think is a pity. There is not one individual scene, there are many scenes, which are very hermetic and do not communicate with each other. I find this very strange. Living here, I started to understand Thomas Bernhard and Ulrich Seidl.

I moved here 12 years ago and I have seen this city change so much in this time. I see this to be a very positive change. Vienna has become much more international. Have you noticed any changes since you came 2 and a half years ago?

NS: Yes, definitely. The best change was the perspective change when I moved from the 2nd to the 10th district. Now I like the city even more. It has something to do with my job being director of a public institution, I guess. I would not want to live in these popular districts. You are constantly in the spotlight there, being watched. It’s not possible to go out somewhere privately as you always run into someone who you know, who tells you what you should or shouldn’t do. You really have to fight for your privacy in this city.

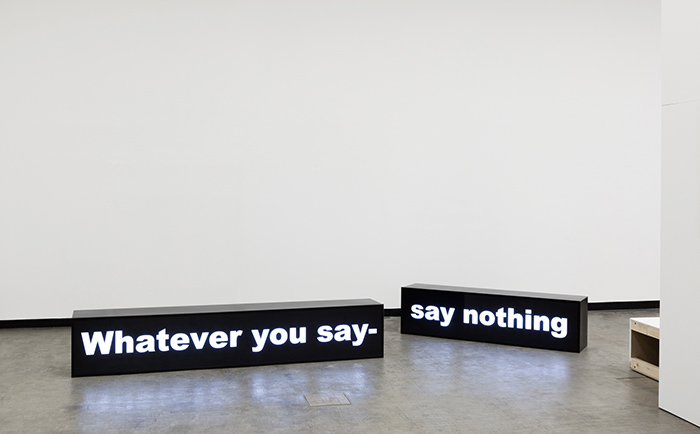

Exhibition view New Ways of Doing Nothing © Kunsthalle Wien 2014, Foto: Stephan Wyckoff: Gardar Eide Einarsson, In Taxis, On the Phone, In Clubs and Bars, At Football Matches, At Home With Friends, 2013, Courtesy Privatsammlung, Oslo and Yvon Lambert, Paris

What development would you like to see in the city in the future?

NS: The attitude toward migration should definitely change. It should not be important where people come from. Especially in this religious system, the attitude should be more positive. But this is not just a problem of Vienna, it is a problem concerning Western countries in general. There is something very wrong with the way things are going. I think it has to do with architecture as well, so the architecture has to change: where our representative bodies are, our schools and universities, our religious buildings. There should be much more dialogue between different groups. We need spaces for an open discourse. I wish that the native Austrians (people who have been living here for generations) are more open to change. Look at the poster of Ken Lum at the Karlsplatz, it promises exactly this change that I’m speaking about.

Ken Lum, Coming Soon, © Kunsthalle Wien 2015, Photo: Maximilian Pramatarov

Are you happy in Vienna?

NS: Vienna is not the only place I live. I also live in Berlin. I know that I’m in a privileged situation where I can afford two places and I appreciate it enormously. I have always lived in many places and could not live in only one city. I guess I need that distance and perspective. But I’m happy to be in Vienna right now and I hope I can add to the positive changes in this city.